One hundred years ago, Douglas Starch Works erupted like a powder keg, shaking the city of Cedar Rapids so violently some thought the Germans were bombing America’s heartland. Forty-three workers from the evening shift died that May evening, though new plant worker John Griffin was miraculously spared, as he decided to walk back to his nearby home for supper. For him, it was a near miss, though he would have to live with the memory of pulling his coworkers’ bodies from the smoldering rubble.

Roughly 50 employees suffer fatal injuries at work annually in Iowa or almost one per week. In 2017, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tallied the total U.S. number at 5,147. Globally, 2.3 million die a year due to work-related injury or illness, or 6,000 a day, according to the International Labour Organization. But no one can really tell how many near misses there are, how many times someone courts tragedy, and instead of slipping in a puddle and falling down the steel stairwell, merely loses their balance. Few are inclined to report an “almost” bad thing unless they just avoided a horrific event like a plane crash or factory explosion. That’s an excellent conversation starter. Conversely, pedestrian near-misses carry a stigma—and negative consequences, notes Charles Douros, senior consultant for ProAct Safety.

In a piece he wrote for our sister brand EHS Today about near-misses (which OSHA defines as “an unplanned event that did not result in injury, illness, or damage—but had the potential to do so”), Douros writes “if it occurred because someone ignored or neglected a safety procedure, there might be a reluctance to report it for fear of reprisal. It’s essentially a lagging indicator—something bad has already happened and now the company is forced to react to it.”

It’s bad business to be reactive. You should always strive to be the one who knocks, lest you be the one who gets knocked over. Manufacturing and other industrial sectors already practice this with their mechanical assets, having spent the better part of the decade developing tools and software to help them preempt disasters and downtime using data. We’ve covered this so frequently within these pages that it seems predictive maintenance startups are as common as Starbucks or mattress stores. But how often is that courtesy extended to the fleshy, less robust productivity drivers in the plant or facility, the ones who have pain tolerances and families and lawyers?

Today, there are not many data-forward solutions to help plant managers avoid near-misses, let alone injury. But Gabriel Glynn, the great-grandson of John Griffin, is set to change all that. The Des Moines-based company he co-founded, MākuSafe (pronounced “Make-You-Safe”), provides workers with a sensor-stuffed wearable device worn above the elbow that collects all sorts of vital environmental data, from noise to light to temperature. The data are then transmitted to the charging kiosk/edge device, which then sends the info to the cloud. This is where the MākuSmart software correlates location and environmental data, combing through real-time sensor data to find anomalies and potential dangers. Over time, with enough training of the software to recognize a company’s cadence, the system promises to identify dangers and OSHA violations before they happen.

The device is in five facilities now and will be available in Q1 of 2020, at a cost of about $22/month per device. The battery life is about 24 hours, so two workers can use it in the same day. The national worker’s comp bill per month is almost $5 billion, so it's a good deal.

We’re in the throes of the IIoT revolution, so plants and other facilities probably have sensors abounding, though they can be mounted on walls hundreds of feet away from the action.

“In a matter of a few feet, the environment can be totally different,” Glynn says. “Depending on what side of the machine you stand on, the sound exposure can be dramatically different.”Using humans as a sensor allows a more exact mapping of the environment, allowing managers to go from a rough Google Maps snapshot to a detailed Google Street View look at their operation. And this then promotes action. If a new machine generates more noise than anticipated, up the hearing protection. Maybe the TVOC sensor alerts to higher levels spilling out of the paint room, which means it might be time to investigate the ventilation. If an area’s temperature spikes, it might be time to relieve the crew for a water break. And if you leave the device in your car in the summer heat, it will make your team think you’re on the face of the sun, as Glynn recently found out.

“We’ve come a long way from 100 years ago when factories were exploding due to starch dust, but there’s more we can do,” says Glynn, a serial software entrepreneur who previously started and sold a mobile ERP company. “It feels predestined that a hundred years later I would get to work on a product that was designed to prevent these kinds of things.”

It’s as much industrial pedigree as fate for Glynn, whose father—a former machinist and longtime safety manager—taught him the value of a safe, healthy worker to the overall company. Glynn got the idea for the wearable about five years ago after talking with his dad about the OSHA auditing process for lost hearing. Being around industrial safety for a better part of his life also informed Glynn on industrial rules such as no wrist or neck-worn accessories, which could snag on equipment. The armband is designed to tear away from the wearer if caught on something.

Armed with this familial knowledge, combined with this recent work running the Advanced Manufacturing Podcast where he visited several factories and workers, Glynn knew environmental safety was ripe for disruption. And this solution would be a win-win for workers and plants.

“My Safety Sense is Tingling”

“Fatigue is the leading cause of accidents and the environment is the leading contributor for fatigue,” Glynn says.

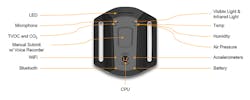

Logically, if you want to address accidents, which occur 500 times a minute around the world, you attack the environment. Glynn and fellow co-founder and CTO Mark Frederick, who does the heavy lifting on the hardware side, made sure the MākuSafe wearable absorbs just about every imaginable piece of environmental data to keep workers safe and productive.

It has an accelerometer to detect slips and falls, a noise dosimeter to pick up auditory danger, a visible and infrared light sensor to ensure work zones are properly illuminated, and temperature and humidity sensors to verify work zones are safe and dry. The pager-sized device also tracks CO2 and total volatile organic compounds (TVOC) levels, the latter of which could cause immediate or long-term respiratory issues. If that weren’t enough, Glynn says the patents leave room for several other sensors in the future.

And MākuSafe doesn’t miss near-misses.

“If a guy trips on crack on the floor, our device picks that up and records it on their behalf,” Glynn says. The machine learning within the cloud-based backend, MākuSmart software, has been trained to look for when the accelerometer hits above 2 g and the arms move back and outward, or other wild gesticulating indicative of a losing one’s balance. That sends an alert, along with time, location and user, to the safety manager’s mobile device app, who can address the incident with the employee.

An early pilot validated this real-time system. Glynn recalls the device recorded the slip and the safety manager verified that is what happened and investigated why. A mat between two machines was too short, leaving a gap that clearly created a tripping hazard. A new mat was quickly put in place to eliminate the danger.

Ordinarily, a wet spot on the floor or crack in the concrete would be overlooked unless it resulted in a serious injury. That takes time and time is money.

“Employees don’t want to stop their work and spend 15 minutes filling out paperwork for an accident that didn’t even happen, says Glynn, who independently verified OSHA’s findings that 80-90% of near-misses go unreported. “They have quotas to meet.”

Not every near-miss can be recorded by the suite of sensors, but a human’s senses would, such as if a pallet full of material were to fall from a high shelf near a person. This could easily result in loss of life, but the loss of productivity can be more pressing if your safety culture takes a backseat to the bottom line.

MākuSafe prepared for this eventuality with a voice recorder that can log the incident with the push of a button. All the necessary data, from who reported it to all the environmental context, gets sent with the voice memo, which is translated to text and put in the incident report. This costs 15 seconds of worker time and is invaluable in finding and catching potential hazards to the works. The relays have a range of about 100 m, and if the worker is beyond that, or working in an enclosed space such as a freezer, the data is stored on the device and sent when within range.

This not only keeps workers from missing time, and the company losing productivity, but helps foster a healthier safety culture. It’s a technological take on a good catch program, a more positive look at near-misses as opportunities to continuously improve.

“Employees can feel very good about taking some measure of action to potentially prevent a bad thing from happening,” concludes Douros. “It’s an opportunity for employees to see the potential for an injury before one happens and do something to address it. There is usually no stigma attached to this program since it isn’t blame-based.”

Forecasting Disaster to Prevent It

The value of a wearable safety device, whether it’s the MākuSafe that detects ambient data, or the ear-worn Bodytrak device, which focuses more on physiological data analytics (and also includes fall detection), is that they convert traditional lagging indicators, which tell you how something got screwed up, into leading indicators, which help avoid the screwup entirely.

Glynn, a native of Iowa, likens it to the evolution of how the National Weather Service has evolved to warn people about tornados.

“When I was a kid, the siren would go off and you’d look out the window and there’d be a tornado right there and you have 10 seconds to get down the basement,” he recalls. Because of new satellite and radar technology, things are vastly different now. Glynn notes that this summer he received a tornado warning days ahead of the expected touchdown.

Glynn says it’s just as crucial for plant management to predict which way the wind will blow within their factories.

“Knowing the environmental conditions and how they change, when they change, and what the impact is on the worker gets us to a place where we can forecast risk and identify things well before they present a risk to the worker,” he says.

He projects that as the technology evolves, the alerts sent from the device to the MākuSmart system will initiate automated responses, such as starting the air system up when humidity reaches a certain level that could create condensation and a slippery floor.

Preventing falls is the obvious use, and a reason EMC Insurance Companies, also based in Des Moines, is running a pilot with MākuSafe, which identifies itself as insurtech (insurance technology).

“The world’s changing for our agents and policyholders,” says Bryon Snethen, EMC VP of risk improvement. “We want to provide them value beyond insurance; wearable technology and effective data analysis are some of the ways we’re pursuing that.”

While that testing is still ongoing, the basic calculus works from a cost-benefit standpoint. Worker’s compensation claims cost $1.2 billion per week in America, a huge reason why the industrial safety market is worth $3.3 billion and will grow 64% by 2024, according to MarketsandMarkets Research.

An average wrist injury, likely due to a fall, can cost $50,000. It makes more sense for an insurer to outfit the factory with MākuSafe’s devices and software as a service for about $20,000 a year for a factory of 150 (if employees share the devices). If the solution prevented one such injury over two years, the insurer saves $10,000.

Productivity as a Byproduct

As with any new stream of data, the benefits aren’t always clear-cut or obvious. That accelerometer has uncovered more than just tripping hazards. Glynn says that a test at an industrial laundry facility alerted management to odd jerky motions every hour or so at the bottom of a chute. They investigated and found the design of the fixtures was causing a laundry clog, which workers would have to tug at to free. They expended more energy than necessary on vigorous repetitive movements, which could lead to arm injuries over time. And in the short term, it created a material bottleneck. The problem was fixed, and productivity increased.

“The more we understand the environment and what the optimal conditions are, the more efficient and productive workers can be,” Glynn says.

Worker’s comp savings can be hard to predict for a specific factory, and therefore a hard sell when so many other areas of the plant need digital upgrades to increase revenue. But in theory, wearable safety tech should improve a host of productivity KPIs as well. An increase in machine uptime could be one of the more noticeable happy byproducts.

“Eighty percent of equipment failure comes down to human operator error,” says Jim Stuart, senior vice president of digital products at Lloyd's Register.

Lloyd’s recently came out with the AllAssets Asset Performance Management (APM) platform to manage these risks from the machine side, using machine data, digital twins and the cloud-based, SAP S4HANA SaaS to reduce planned maintenance in oil & gas and shipping by more than 20% and avoid catastrophic machine failures which at worst cause injury or death, but more likely will create machine downtime and a loss of productivity.

Machines are only half the battle, though. His company is now investigating a solution similar to MākuSafe to complete the three-pronged strategy to address worker fatigue and reduce accidents. The first two are training and preparedness, controllable enough variables due to processes in place.

“The most challenging part is humans’ interactions with environmental challenges,” he says.

He says more actionable data, from both machines and people, will be critical to addressing that challenge.

“Being able to stream real-time data means that you can get to insights much quicker and you can intervene much quicker as well,” Stuart says. “So, I think all of that stuff's going to have a positive impact in terms of reducing safety risks and improving performance.”

Culture Shock

Avoiding death and dismemberment are the obvious reasons to institute a more data-driven safety strategy, but not everything is life-and-death. The positive impacts on employees are often more subtle but can be more far-reaching. Even if the safety manager investigates an alert from the MākuSafe app and realizes it’s perhaps human error or a false alarm, these interactions improve the plant culture by creating conversations outside of the mandatory training sessions which Glynn relegates to: “It’s March, let’s take out our binders, we’re going to talk about heavy lifting for two hours.”

This allows safety managers (like Glynn’s dad) to “identify real problems specific to them and build that culture that is vital to the attraction and retention of employees,” he says.

And open communication is one path to destigmatizing accident reporting that just might work, though it’s weird to think this is a novel idea when nearly everyone shares way too many facets of their lives on social media, from their gourmet mac n’ cheese to their crudely drawn tattoos. While the digitally native Gen Z, which is poised to own a plurality of the workforce at 40% next year, love texting and Snapchatting and WhatsApping, they want feedback in person. A Kronos survey found three out of four prefer face-to-face manager feedback. If the manager can use technology-driven data to back up a safety counseling session, all the better.

“The more employers can do to make jobs safer and more pleasant, and allow workers to not get fatigued as often, the can retain and attract a better workforce,” Glynn says.

It’s also a great way to show current employees their worth and keep them from seeking a new environment.

“Employees will go down the street for a variety of reasons, and because of that competition, the value of the human worker has never been higher in my entire lifetime,” Glynn says.