This is a continuation of "Style & Substance: The New Wave of Industrial Wearables":

When we ended Part 1, Intel had already used a very effective picking solution for its Recon Jet Pro smartglasses pilot, but to fully leverage the hardware’s power and capabilities, the world’s largest chipmaker needed more. It needed a partner to come in and perfect the Jet Pro’s SDK.

Because, let’s face it, if you could have an awesome platform, but without awesome applications to take advantage of the computing power, what do you have? In the case of the Recon Jet Pro, you have $600 safety glasses.

And the enterprise wearable software has an even tougher task than their consumer counterparts. Augmented reality apps for the HTC Vive or Samsung Gear just have to be interesting; industrial models have to demonstrate a return on interest.

For that, Intel turned to Upskill, an enterprise wearable solution provider based near Washington, D.C., that started out providing HUD apps for the Department of Defense.

“There has to be a key value proposition driver in a business metric that’s tied to it in order for this to really take off,” says Jay Kim, the CTO of Upskill.

We actually featured Upskill in last February’s cover story—”2016: The Year of the Wearable.” The story, written by editor Travis Hessman, was all about how we may have turned the corner from “goofy monocles” to functional devices, and how 93% of companies were investigating wearables.

But they were still called APX Labs. Last year, like Recon and the wearable industry as a whole, it grew up. Now rebranded as Upskill, (because it elevates worker output), the company has gone from a cool, agile tech startup to a bonafide wearable leader, with the mission of enhancing the industrial workforce in a more connected digital world.

The company’s Skylight software platform has been the go-to enterprise solution for Johnson & Johnson, GE and several other major companies in their logistics, field service, and manufacturing operations.

It serves as the connective tissue between workers, the IoT, HMIs, ERPs, MRPs, and every other relevant industrial acronym, creating and running the necessary work instructions, tasks, and digitized data through a wearable to make the worker’s job as easy and error-free as possible.

At Boeing, Skylight-powered pairs of Google Glass completely eliminated the need for wire harness assemblers to constantly look over at paper instructions or a laptop for the next step. Instead they could view the instructions in the display, and use voice commands to proceed. All the while, they kept both hands twisting and looping miles of wires that will eventually end up on an aircraft. Boeing says the solution cut production time by 25% and reduced errors to almost zero. (Maybe Glass wasn’t such a disaster after all.)

A similar test at a GE Healthcare warehouse in Florence, S.C., produced a 46% improvement during a picking operation.

“In just three to five years, I can’t imagine a person on the plant floor that doesn’t have a wearable device to help them do the job,” says Paul Boris, VP of Manufacturing Industries at GE.

And the list of wearable companies is growing out, “and that’s a good thing,” Kim says. But that doesn’t mean we’re on the verge of giant holographic screens projecting before our eyes or really immersive applications in that period Boris spoke of.

“For at least the next three to five years, the sweet spot in enterprise wearables is going to be delivering preexisting information within their database in an assisted reality fashion to create a hands-free computing environment,” he says.

So was 2016 really the year of the wearable?

It’s more like the year they came down to Earth, believes the pragmatic Kim, who we also interviewed last year and who urged folks to look at industrial wearables as tools, more related to torque wrenches than iPhones.

And he thinks companies are finally seeing it that way, too.

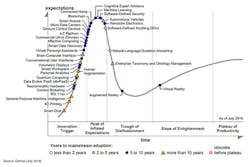

“I would reference the Gartner Hype Cycle and say that this is an industry that is getting out of the trough of disillusionment,” Kim says. “The companies we engage with have really turned the corner from the innovation side of the house to the plant managers and operations managers who have a business need to solve.

Gartner Hype Cycle

“You had the early adopters that have learned their lessons and are engaging with us and others within the ecosystem,” Kim continues. “The market as a whole is moving from initial pilots into meaningful deployments.”

And that’s precisely what Intel was looking for. Upskill doesn’t simply build a custom app and send you on your way. They run their fingers up and down every inch of a company’s structure to find the pain points, like a digital masseuse.

“We go deep into a company’s way of how they work and how they access the information,” Kim says. “And that means getting to the very core of the data sources that people are using within a factory or warehouse on a day-to-day basis.”

And just as smart glasses aren’t much good without functional software, data isn’t much good without people to use it. Wearables are the bi-directional interface that provide the data and access it.

This is why Croteau calls wearables “the last 15 feet” of a truly smart factory.

“So you’ve automated your plant, you’ve got sensors on everything, you’re pulling out all this information about your production and your workflow,” Croteau explains. “And the last piece of your manufacturing facility that’s not connected is your worker.”

Now, running a solution such as Recon Jet Pro and Skylight, your workforce is finally dressed for success.

And maybe we’re looking at wearables all wrong. They aren’t tools and they aren’t weapons. They’re doorways to a world where we don’t fear automation; we domesticate it.

“The key is that technology can be a friend, not a foe,” says Marco Annunziata, global economist and executive director at GE’s Global Insights.” Many see Artificial Intelligence as the biggest threat; but invariably we find that a human and a machine together beat a machine alone every time, no matter how smart the machine.”