Ergonomic Economics: How to Inexpensively Reduce Material Handling Injuries

Overexertion injuries aren't just putting a strain on workers' musculoskeletal systems. These nagging injuries in the neck, back, and upper and lower extremities cost American companies about $15 billion a year in direct costs such as medical fees and indemnity payouts, according to the Liberty Mutual Workplace Safety Index.

The indirect cost—which includes lost wages for the employee, loss of productivity for the company, and the cost of retraining new employees—is much harder to pinpoint, says Jim Galante, chairman of the EASE Council, though he says most ergonomics experts place it between four and five times the direct cost.

That means these musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are indirectly costing at least $60 to $75 billion.

Practitioners agree that 40 to 70% of workman's comp claims are related to manual material handling. So even on the low end, that's about $6 billion. Quadruple that for the indirect cost of $24 billion, and you get a very conservative estimate of $30 billion lost to material handling injuries.

These include relatively minor injuries such as Carpal tunnel syndrome, which costs around $6,000, to serious back injuries, which can cost up to $90,000.

That money isn't lost if you work in the healthcare industry or manufacture pain pills. Those businesses are booming. But what about the small industrial companies who for so long have been the backbone of the American economy?

"Small companies just don't have the access to the professionals," says Galante, who is also director of Business Development at Southworth Products. "Very few have the benefit of an ergonomist. These small companies don’t have the healthcare pros that Ford may have."

Instead, they have human resource managers trying to implement some sort of training as best they can. The government provides some extensive guidance through the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), but that's like handing a journeyman electrician the schematics to a nuclear reactor and saying, "All the info you need is right here; create a safety plan."

These manuals are up to 300 pages long and "well done," Galante says, but "the employment manager or HR person isn't going to get past page 3. The information published is very complicated and needs to be used by a practitioner."

So if what Galante and other ergonomists say is true, we have a majority of workers at risk for serious injuries, and a majority of companies at risk for financial hardships, and there's no way to fix it.

If you work in the industry, you know there's always some way to fix broken stuff. That's pretty much all you probably do. And our job is to provide you with the tools to fix stuff.

And we're happy to do it. Well not us exactly, but we asked Galante, who has nearly five decades of experience.

"There are some tools out there to help the small guy," he says. And he was kind enough to provide some of his favorites.

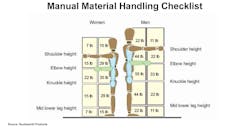

Let's start a basic checklist:

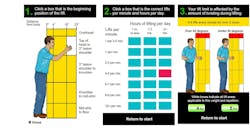

And the Oregon OSHA has a very handy interactive Lifting Calculator app for desktop and mobile platforms. Click here to access it. look below to see a step-by-step how to use it.

And here's the NIOSH Lifting Equation.

And for pushing and pulling, look no further than the Liberty Mutual Manual Material Handling Table, an online tool to "provide both the male and female population percentages capable of performing manual material handling tasks without overexertion, rather than maximum acceptable weights and forces."

The important thing to remember is that merely glancing at an app or running a calculation isn't enough.

Once you calculate what your material weight, repetitions, and height requirements are for each handler, you should take a look at equipment to help you do the job. Most of these tools are simple to use and inexpensive, especially compared to what a worker injury could cost you.

Pallet Lifter

"Generally speaking, when you're dealing with pallets, you need to do two things: raise and lower it, and rotate to eliminate the reach," Galante says. "Reaching out is actually worse than back bending."

Southworth's PalletPal line accommodates more than two tons, and adjusts as weight is added or removed from the table, so the load is always at an optimal height. They also rotate to keep the worker from having to reach. They range from pneumatic to spring-loaded.

Lift Tables

A taller pallet, a seven-footer for example, requires a different solution than a simple spring-loaded solution. Installing a lift table that goes into the floor may be the better option.

"Drop the bottom two-thirds into the floor, so 30 to 40 inches is in the magic ergonomic window," Galante explains. "People are less likely to hurt themselves and biomechanically the strongest they can be. It doesn't matter how tall you are; everybody's knuckles are about 30 inches off the floor."

Container Tilters

Containers can be as large as 30 x 40 X 48 inches, so repetitively bending over to reach a product in the far bottom corner increases the risk of an MSD.

Galante advises thinking about what will go in the container, from wire baskets to steel pipes, before choosing what type of tilter. Some have an elevated hinge to keep the loads at the right handling height.

There's no one solution for everything. Those choices are affected by a man or woman, how many times an hour a day they do it, the temperature or if it's a wash-out environment.

Work Access Platforms

Galante says lifting the worker, not the workpiece, is a more recent trend of the last five to seven years. It's good for working on plane wings or giant heavy machinery, he says.

"If a guy is wiring a large electrical panel that’s seven-feet high," he says, "it makes more sense to raise worker so the top of the panel is 30 inches above where he is standing. Put the work zone in that 30-inch window for him to do his job."