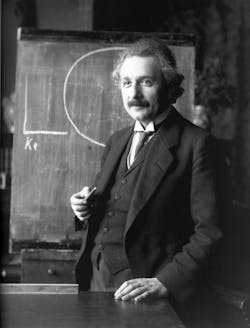

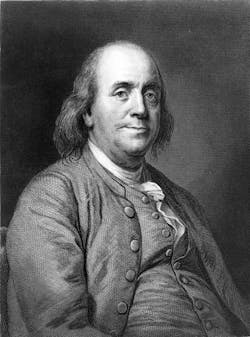

I was recently given a copy of Melissa A. Schilling’s book Quirky, “the remarkable story of the traits, foibles, and genius of breakthrough innovators that changed the world.” More specifically, it focuses on people who had multiple breakthrough innovations that changed the world. Incredibly well-researched, the book walks readers through the lives of eight serial innovators: Marie Curie, Nikola Tesla, Dean Kamen, Albert Einstein, Steve Jobs, Thomas Edison, Elon Musk, and Benjamin Franklin.

Quirky illustrates a common thread among these geniuses and asks whether it’s possible to teach someone how to become one of the greats. In short, no—it isn’t. However, there are things that could aid or create an environment to yield people who are more aware of (and capable of) innovation on a grand scale. The book relates some great stories and details of these serial innovators’ lives, noting the following commonalities:

Melissa A. Schilling

A Sense of Separateness

Many serial innovators experience some degree of social isolation, especially while growing up. Having time alone can give people the space to process the world around them without external distractions and cultivate original thought. And doing so can free a person from the constraints of established solutions to problems.

This reminded me something a director of an innovation center once said: “The great things about creating innovation in young people is they aren’t afraid to try something new, and they know just enough to think it might work.” While people in an industry might walk away saying that it has never been done that way, or couldn’t be done that way, innovators ask, “Why not?”

Credit: Jahangeer Ansari

This was present in Elon Musk’s story in creating reusable rockets for space travel. The industry said it wasn’t possible. Musk answered, “Why not?” Even the namesake of Musk’s company, Nikola Tesla, was told by his college professor that an effective AC motor wasn’t possible. All of which leads to another trait: extreme confidence. After all, if you are going to be told you’re wrong, but decide to continue anyway, you’re going to need a very healthy level of confidence.

Extreme Confidence

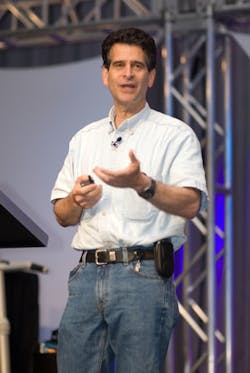

The terminology here is imperative: It is extreme confidence, not arrogance. The ability to believe in oneself to succeed, or self-efficacy, was established in most of the profiled geniuses at a young age. Dean Kamen—a successful engineer who most know for his invention of the Segway and founding the FIRST Robotics Competition—was already making about $60,000 a year when he started college.

Credit: mark6mauno (Dean Kamen) (CC BY-SA 2.0), via Wikimedia Commons

Kamen believes that there are only four things we know for certain: Maxwell’s equations, Newton’s three laws, the two postulates of relativity, and the periodic table. Even Musk’s relations seemed to have this same idea of going against not only social norms, but also man’s rules.

Musk’s grandfather, Joshua Haldeman, was involved in the technocracy movement, which believed that politicians and businessmen should be replaced with scientists and engineers. This idea has been echoed more recently by Neil Degrasse Tyson, who asked why our government has so many lawyers and so few scientists and engineers. While some would argue that most people think their profession would run the world better, I’m biased—I agree with the idea of letting those who better understand how the world works write policy on how to run it.

The Creative Mind and Other Values

Serial innovators are effectively smarter and “crazier” then the average person. This is where we start to see our own dreams of changing the world slip away to an impossibility. The book actually goes into great detail about how the mind of a serial innovator may be functioning.

Rapidly emerging evidence on neurotransmitters such as dopamine, and their effects on things such as latent inhibition and psychopathologies, are often associated with creative genius. As many serial innovators have been rumored to not sleep much, owing to their drive to work, these neurotransmitters may play a role in whether a person has the mental acuity to become a serial breakthrough innovator.

Credit: MetalGearLiquid, based on File:Steve_Jobs_Headshot_2010-CROP.jpg made by Matt Yohe (CC BY-SA 3.0), from Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, these are some of the same reactions in the brain that, when not properly balanced, are also associated with mental health problems. This may further the argument that the line between genius and insanity might be finer, or more blurred, than we think. Perhaps no one shows this more than Tesla who, towards the end of his life fell in love with a pigeon. But let’s focus on something more productive. Some main trends happening in the minds of serial breakthrough innovators are:

- Primary process thinking

- Remote association

- Working memory

- Executive control

- Openness to experience

Fortunately, the book points out that there are other things we can focus or work on the individual or societal level. Building self-efficacy, inspiring grand ambitions, and finding a proper workflow can all help build up others to something that is bigger than themselves. Like the serial innovators an inspiring environment and the right management can help people see the higher purpose and make them driven to work. Creating non-traditional learning or simply having options more than sitting in the room listening to a teacher could have great and lasting effects.

For example, except for Marie Curie and Albert Einstein none of the serial innovators in this book had higher formal educations, and Marie Curie was the only one who was noted as an exceptional student. However, before you drop out of school, all the other serial innovators where avid self-learners and devoured books. They all had access to books and resources to fulfill their passion to learn, explore, and tinker.

Thomas Edison was the least formally educated of the geniuses presented. This hurt him, according to Tesla. He was in awe of Edison due to what he was able to accomplish with minimal education, but soon noted that the lack of education in math and engineering hurt Edison. Apparently, Tesla felt that Edison could have save 90% of his time with some basic functions of mathematics. This might make Edison’s quote, “Genius is 1% inspiration, 99% perspiration,” a little more painful than inspirational. In short, stay in school, but questions your teachers. If you don’t like the answer, or a teacher can’t answer it proficiently, go figure it out for yourself.

Finally, one of the biggest traits common to serial innovators is something we can all work on: access to books and technology. Benjamin Franklin was a lover of books who started the first free public library. Google tried to start the largest online library ever, but ran into copyright problems that created lag. Perhaps they can learn from the birth of Napster and Jobs’ solution to convenience without infringement that is iTunes.

Either way, towards the end of the book there was a point that cannot be overlooked. Many of the innovators were readers. They had access to books and a larger-than-average appetite for them. This is scary, as in the U.S. teachers are struggling for resources, classrooms are filled with outdated textbooks, and free public libraries are being underfunded or even closing. Encouraging access to books and reading programs is the one trait we can alter, or at least support in the list of great serial innovators. Perhaps it wouldn’t breed super-innovators, but will at least produce a more aware, educated, and well-rounded society.