Bloomberg's Michael Schuman believes these frantic attempts to save factories are a distraction from the real challenge of preparing economies and workers for the demands of the 21st century.

Listening to our political leaders, you'd think everyone on the planet works in a factory.

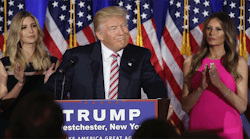

Donald Trump wants to stop China and Mexico from "taking our jobs" by preventing factories from moving there—and he's willing to launch a trade war to do so.

Michael Short, a spokesman for the Republican National Committee, recently claimed that a loss of 264,000 manufacturing jobs under President Obama was "a stark reminder of the failure of his policies," as if the nearly 10 million other jobs added on Obama's watch didn't matter.

This obsession with factories threatens to undermine sound economic policy. The notion that economic strength should be measured by how many assembly lines one country hosts compared to another is based on outdated thinking. And frantic attempts to save factories are a distraction from the real challenge of preparing economies and workers for the demands of the 21st century.

At one time, factories were arguably a good proxy for economic progress. Britain's Industrial Revolution fueled its rise as a world power, just as America's manufacturing prowess propelled its subsequent ascent. In emerging markets today, factories can provide the jobs necessary to alleviate poverty and spur rapid development. China grew into the world's second-largest economy on its foundation of factories. India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi has launched a "Make in India" campaign in hopes of building a manufacturing sector that can absorb the millions of young Indians moving from farms to cities.

But the fact is that in the modern age, it's debatable how much value a physical factory delivers to most national economies. Americans may fret that products like Apple's iPhones are manufactured in China. But in the end, the U.S. economy doesn't appear to be losing out on much. A study conducted by the Asian Development Bank Institute found that the process of assembling an Apple iPhone—undertaken by Chinese workers in China-based factories—accounted for a paltry 3.6 percent of the phone's total production cost. The companies that developed the iPhone's critical technologies and supplied its important components—most of all, Apple itself—captured the lion's share of its value.

That's glaringly evident from corporate profit margins. Apple's operating income was a juicy 30 percent of revenue in its last financial year. By comparison, the same measure at the company to which it outsources much of its manufacturing—Taiwan's Hon Hai Precision Industry—came in at only 3.7%.

It's also doubtful whether factories will remain an important source of new jobs in the future. Automation, advances in robotics and artificial intelligence are making it possible for machines to perform more and more of the manufacturing work currently done by people, resulting in "dark factories" that don't need lights since only robots work there. The Boston Consulting Group figures that by 2025, some 25 percent of all tasks in manufacturing will be automated, compared to around 10 percent today.

Contrary to popular belief, the "loss" of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. hasn't dealt that big of a blow to overall employment. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of workers employed in manufacturing has declined by 5.3 million over the past 30 years. That may sound like a lot, until you realize that there are 151 million people employed in the U.S. at the moment. Even if those 5.3 million positions were lost today, instead of over three decades, it would affect only 3.5 percent of American workers. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy has done fairly well at creating other jobs. The number of Americans employed in the private service sector has increased by 43 million over the same 30-year time period.

Of course, the workers who have lost their factory jobs have suffered dearly and more needs to be done for them. Most of all, job-training programs, vocational education and colleges have to become better funded, more widely available and more affordable for the average family. That's the only way for workers to upgrade their skills to survive in the workforce of the future. Even if factories remain open, the workers they'll hire will increasingly need more advanced technical expertise.

Instead, the solutions most politicians are proposing will protect the few at the expense of the many. We tend to forget how free trade and global production systems have brought down costs for businesses and consumers. Preventing companies from manufacturing outside the country by imposing high tariffs, as Trump has proposed, will raise prices on many household necessities, damaging the welfare of American families while protecting few workers. The Peterson Institute for International Economics looked at what happened when the U.S. imposed a 35 percent tariff imposed on Chinese tire imports in 2009 and discovered that no more than 1,200 jobs were saved, while U.S. consumers were forced to spend an extra $1.1 billion on tires. At about $900,000 for every job preserved, the cost seems steep indeed.

The fixation on factories isn't just skewing policy in the U.S. In China, Beijing's leaders preach the need for economic reform and innovation, but continue to support wasteful, excess factories in industries from steel to glass, mainly to maintain employment. In the process, they're undermining the health of the financial sector and depriving more productive industries of resources.

Having factories may be better than not having them. But policymakers have to realize that they can't turn the clock back to the 1950s. Rather than advocating policies to preserve the jobs of yesteryear, our politicians should be investing in programs to prepare workers for their more likely future.