It's quiet these days on a Sunday afternoon in the streets of Dongguan, where almost every block outside the center is a factory or housing for workers. A red banner advertising for staff above one plant says it has enough orders to keep production lines busy for a year. Locals say the sign has been there at least two years and it's no longer true.

Only a few years ago, things were very different. Even on Sunday, the streets were busy and the chimneys were spewing pollution. The city was the epicenter of China's export boom. Built largely with money from Taiwan, Dongguan sprang up between Shenzhen and Guangzhou making toys, furniture, shoes, mobile phones, everything.

Almost all of the 8 million people in the city came from somewhere else in China, apart from the 720,000 children born since they arrived. Many, like factory worker Yu, made it their home. Now she is considering moving back to Chongqing in the center of China, which she left 20 years ago.

"This is the worst time ever," said Yu, who saw her earnings almost triple during her time in the province. "The factories hurt by the 2008 financial crisis were the smaller ones, but this time the big ones are affected. My friends in Chongqing have been telling me that the development there is flourishing, and they have been trying to convince me to go back. Maybe it's time for a change."

Yu works at a clothing factory that supplies western brands. A year ago, more than 2,000 workers filled the gray dormitory block behind the production buildings. Now, only about 100 employees remain after the owner transferred most of the production to cheaper Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam.

Yu, identified by only her family name to avoid further trouble with authorities, went with some of her colleagues to the local labor bureau earlier this year to protest the production cuts. She said they were told by officials to be patient and keep quiet. The company hired more security guards to keep an eye on them and ensure there was no trouble, she said.

Dongguan was just one of the cities that mushroomed around the Pearl River Delta south of the provincial capital of Guangzhou, the ancient trading port once known as Canton. Shenzhen, Foshan, Zhuhai, Zhongshan and others all rose from the swampy marshes north of Hong Kong. Today, they form a contiguous industrial sprawl of more than 42 million people that would be the world's biggest megacity.

The industrial revolution they began boosted Guangdong province's economy to $1.2 trillion, more than the gross domestic product of Indonesia. Guangdong still churns out a lot of the nation's manufactured consumer goods—half its mobile phones and 80% of its microwave ovens come from here.

A race to upgrade

Six years ago, if you bought an Apple iPhone or a pair of Nike sneakers, they probably came from Guangdong. But as the days of cheap land and labor recede, the province's businesses are in a race to upgrade or move.

"There's growing pressure along with the rising labor costs and overall production costs," said Li Dongsheng, chairman and chief executive officer of TCL Corp., one of the world's largest makers of mobile phones and televisions, which has already moved some production to central Chinese cities like Wuhan.

More than half of the members of the American Chamber of Commerce in China said the increase in costs was the biggest challenge to their businesses in the country, according to a 2016 Business Climate Survey. About a quarter of respondents said they have either already moved capacity out of China or are planning to do so.

The decline of the old export model has spurred the government to act, both at a national and local level.

President Xi Jinping wants Guangdong to set an example in his goal of moving away from the cheap-labor-and-debt-fueled export model to one based more on innovation, domestic consumption and services, Guangdong governor Zhu Xiaodan said in a written interview. Xi toured the port of Shenzhen in 2012, weeks after he became Communist Party chief, and laid a basket of flowers in front of a statue of Deng Xiaoping, who began China's market opening in the city three decades earlier.

The middle-income trap

China's shift to consumption and services lies at the heart of Xi's quest for new growth drivers to escape the middle-income trap, when productivity and profit margins fail to keep up with wage growth. That's spurred provincial leaders to encourage cities to attract new businesses and upgrade factories, headlined by the aphorisms that China's administrators are fond of.

"Empty the cages to welcome better birds," demanded former Guangdong Communist Party Chief Wang Yang, meaning let the old industries leave and replace them with new, higher-value ones.

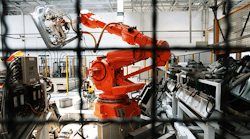

"Replace humans with robots," added his successor, Hu Chunhua, 53, one of the youngest members of the Politburo, in a 950 billion yuan ($144 billion) plan to upgrade 2,000 companies in three years, the official Guangzhou Daily reported in March 2015, adding that the move is not expected to cause heavy layoffs.

Dongguan replaced 43,684 workers with robots in 2015, cutting costs at those factories by nearly 10%, according to the local government.

Lu Miao, a vice general manager of Lyric Robot in Guangdong's Huizhou city, said the government pays as much as 50,000 yuan to Lyric's customers for each robot they use to replace workers.

"The government at all levels in Guangdong has been encouraging companies to replace human workers as rapidly as possible," said Lu. "I can see our business increasing more than 50% this year."

The ultimate result is so-called "dark factories" that don't need lighting because only robots work on the production line. TCL has such a plant making LCD displays, Li said in an interview at the company's headquarters in Huizhou, about an hour's drive from Dongguan.

"For society at large, some workers will be laid off," said Huizhou Mayor Mai Jiaomeng. "But it's good for companies to improve their competitiveness."

Washed out

Local officials say the layoffs are under control, but are reluctant to provide details on how many plants have shut or moved away. A municipal report from Shenzhen in January said that the city has "washed out" or "transformed" more than 17,000 low-end factories over the past five years.

Instead, officials point out how Guangdong province is attracting new businesses, especially entrepreneurs, and building campus-style high-tech parks that are a far cry from the pollution-choked factories of the region's industrial heyday—a program dubbed "to plant beautiful trees to attract the phoenix."

Huizhou announced it will spend 1 billion yuan annually to attract talent by providing free villas and granting cash awards, hoping to lure more than 1,000 PhD graduates in the next five years. But nowhere in the province has been more successful at the transformation than Shenzhen, the city bordering Hong Kong where China's opening first began.

The city of 11 million people boasts one of the largest concentrations of tech startups in China, where salaries for senior staff are similar to those in Silicon Valley. The local government offers cash rewards of 6 million yuan to "outstanding talents."

It's also home to some of China's most competitive companies, from internet giant Tencent Holdings Ltd. to telecoms-equipment maker Huawei Technologies Co. and drone-maker DJI Technology Co.

But across Guangdong, most cities are struggling to match the transformation in Shenzhen. Many are counting on an older investment model to sustain growth: government spending. The province said it plans to invest 1.43 trillion yuan—almost the GDP of Greece—in the next five years on 158 projects to improve infrastructure.

Addicted to cheap goods

The race to reinvent industry in the Pearl River Delta masks a fundamental drawback for China's industrial base and the consumers around the world who have become addicted to cheap Chinese goods.

Guangdong for three decades created one of those rare periods in industrial development where everything came together in the same place at the same time—capital, cheap labor, infrastructure and relative freedom from controls. The world's biggest ships, carrying up to 19,000 containers, could dock in Shenzhen and fill up with goods for all over the world, none of which was made more than 100 miles away.

By moving elsewhere in China, factories may be able to trim wage bills or gain access to cheaper land, but they lose the concentration of suppliers, logistics and services that Guangdong has built up over 30 years.

Gao Dapeng, CEO of Desay SV Automotive Co., which makes car navigation systems in Huizhou, said the overall cost saving of moving to an inland province like Chongqing is only about 10%, and it would mean the plant would be hundreds of miles from its suppliers. He said the company is not sure if the relocation is worth that.

Yet factories in the province continue to close, stirring discontent.

The number of strikes and protests in China doubled last year, according to the China Labour Bulletin. Among the 886 incidents recorded in manufacturing, 267 were in Guangdong, three times as many as the next highest province.

Last year, thousands of workers protested on the streets of Dongguan when Microsoft Corp. decided to close the old Nokia factory that had been operating since the mid-1990s.

Rising discontent has brought a tough response from city officials, according to some workers, who asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation. They said their mobile phones were being monitored by the government.

"None of us likes this situation we're in but we didn't have much choice," said Yu, the factory worker. "The factory owner was going to run out of cash, and the government should take some responsibility."

Like many of the companies, Yu's biggest drawback with relocating home to Chongqing is the cost and the upheaval. Her son is in high school and her husband runs a small local restaurant.

With the new robot-staffed factories, and startups that employ hundreds rather than thousands, many of the millions who came to make Guangdong an industrial superpower may have little choice but to return home.

For Jerry Yang, a production-line manager in his early 40s whose employer has slashed output, that feels like a betrayal. "I sold my youth to Dongguan," he said. "And look how it treats me."