By now, we all know the advantages of 3D printing parts. From prototypes to end-use parts, you can make anything you need, anytime you need it... so long as it fits in the build area. There are no geometrical restrictions, no limits to complexity—the extruder will manifest anything your CAD skills allow you to design, from spherical latticed doodads to spiraling, Escher-inspired blocks. Plus it also lets you get by with a virtual inventory, as a reserve can be created on-demand.

The process isn't quite as easy hitting the old Windows command, CTRL + P to spit out part, at least not yet. The problem is, like when a conventional 2D printer converts the digital to physical, growing a brand new 3D-printed part has an unavoidable consequence.

"Once the part is printed, in some ways the digital link is broken," says Andy Kalambi, CEO of Rize, Inc.

Severing the lifeline to the digital twin removes all the benefits that being digital offers, he explains. An entire enterprise, and beyond, can track a part in cyberspace from CAD drawing to the umpteenth revision, knowing who designed it, who manufactured it, and how to maintain it. It's accessible on PLMs and other databases, and provides precise design and material attributes all the way downstream to the assembly person.

But once you make it real, it loses that power. You could throw a 3D-printed widget in a pile with similar, but not exact looking pieces and not really be sure which is supposed to be for the front or back of a subassembly, or which was the old version with the defect, or how old it is.

"If you open piece of equipment and look at a part, it's not talking to you," says Kalambi, which is a problem when so much investment is going on to make plants and factories smart. "If it fails and you need to replace it, you need to have some intelligence on how to dismantle it or how to remove it and if you need to make it again, you need to know the material."

Additive manufacturing is a crucial cog to the digital transformation and lingering questions like these are huge impediments. That's simply not something Kalambi can abide. So he and his company are doing something about it.

Rize Up

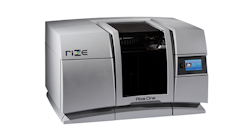

Rize is a recent addition to the additive industry, manufacturing desktop 3D printers known for nearly non-existent post-processing, isotropic Z-strength, and voxel-level ink printing on the part.

Kalambi, however, is no newbie. He worked for ERP developer SAP in the 1990s and Dassault Systèmes—maker of 3D modeling and PML software—until last winter. Which means he has been in this fourth industrial revolution, and the digital transformation it requires, since the very beginning.

From this perspective, he sees an absolutely inextricable relationship between manufacturing and the digital world. And additive parts cannot lose that connection.

The solution Rize has come up with is deceptively simple: jetting QR codes onto the print to create a Digitally Augmented Part.

Integrating QR codes on to these physical pieces creates a unique signature that reestablishes the link to the digital twin by calling up the XML-based 3MF file. All someone has to do is wave their smartphone or tablet over the part and, voila, instant information on technical specifications, where it was made, and even work instructions on how it fits into an assembly.

With this feature, a machinist several degrees of separation away from the team that 3D printed a clamp, for example, can still have access to vibration tolerances, how to install it, and any other special instructions the part may need.

"You can take all the relevant info and put it in part, and it's completely tamper proof," Kalambi says. "The ability to 3d print in this information enables you to deploy blockchain into the 3D-printing process and ensures the IP capture is completely immutable and cannot be tampered with."

Until now, the Rize One printer's ability to overlay text, logos or designs with the blue ink has been a useful branding tool for the company and its utilitarian functions include marking a full SKU number or actual instructions such as "This End Up." The major innovation has been that this is done at the voxel level so the code is deeply embedded, as much a part of the part as a tattoo is on the skin. This means, even in rough industrial environment that would normally cause a sticker to peel off or manually applied ink to smudge or scratch, this marking remains indelible and pristine.

And this, barring severe damage of the part, allows everyone in the chain of custody to alight that physical object right back to its digital twin.

Staying on Track

"Traceability is of crucial importance," says Kalambi.

For medical-grade parts derived from its thermoplastic Rizium One material, that reason should be obvious. Aerospace, which Rize has also moved into, also has stringent chain of custody requirements. For these two industries, traceability has always been paramount, and Rize's new method—announced just this April already has people excited about how it will reduce confusion, and possibly errors, in the design process.

"Our process for the development of new products generally requires numerous iterations to get the part features just right," says David Perron, Group Manager at CONMED, which makes medical devices that are used in arthroscopic surgical repairs. "The changes are not always obvious, particularly when we're looking at dozens of iterations. The QR code will help us to easily identify iterations and show the flow of the design thought process."

Kalambi says the QR codes should streamline and speed up product design. When two engineers are assigned different components, such as a front and back end, they aren’t always working at the same pace. Because the digital thread remains, the engineer ready to print can do so, put on smartglasses that read the marking and will overlay the side that only exits digitally to render a complete assembly. This gives the team a clear view if the designs match and will fit together. Any mistakes can be caught early on.

The augmented parts will also allow a design team to quickly switch from physical to virtual reality. The code can directly link to the CATIA V5 CAD file for a designer to virtually manipulate the digital twin. It's not game-changing, but it is convenient. It also ensures the 3D model being changed is the correct one, as each new part gets its own unique code.

In the Field

AR and VR are fairly high-level uses, though alone, probably not what will make companies run out and buy a Rize One. There are plenty of great reasons, from the isotropic parts strength along the X,Y, and Z axes, modest price around $30,000, and the breakthrough that earned it an NED Innovation Award last year: jetting a special release layer between part and support so you can manually separate the two, rather than dipping it in a chemical bath or chiseling away.

By putting these together, what Rize has done is build more trust in 3D-printed parts. Enough trust, in fact, that these parts could soon appear on the front lines with U.S Army.

"A system can go down because of one missing part and something like 3D printing that can get you back in the fight. That's a huge benefit to the Army," says James Zunino, a materials engineer at the U.S. Army Armament Research, Development & Engineering Center at Picatinny Arsenal in New Jersey. "If a handle is broken on purge pump or wheel is damaged on an EOD robot, you could in theory print a new one."

His team has worked with several 3D printers, from $500 dollar machines to those worth over $500,000. He pointed out how useful Rize's simplified post-processing would be in regions where water resources can't be wasted for cleaning parts and that the new augmented parts add an extra layer of confidence.

"I think having accountability and provenance of a part is huge in the general acceptance of AM parts," Zunino says. "A lot of it is trust in the new technology and this really helps build some of that trust."

Considering one of the assets that could be 3D-printed is a grenade launcher, knowing that an experienced technician made it (and not a first-year grunt) is something a field commander would want to know.

In the end, knowing really is half the battle.

"Would you buy a vehicle if it didn't have a VIN on it?" Zunino asks. "You'd probably question it."