When Frank Marangell, an experienced 3D printing executive, was researching whether to join a startup Rize, Inc., he realized the innovative technological and materials approach to rapid prototyping excelled in several areas. He ranked them as follows: Strength, surface finish, color, zero-post processing, and environmental.

It wasn't until the former president of Objet and current Rize CEO did some market research that he found that the company was burying the lead.

"What was that fourth one?" he recalls the various industrial types asking. "Zero post-processing. That's the one that really hit home. That's the one where the pain is really there. These people, most of whom were making prototypes or manufacturing jigs and fixtures, wanted to know how we were going to save them from having to come in on weekends to do post-processing."

On the lighter end of the post-processing spectrum is Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). This requires removing support structures, light sanding and/or soaking.

"The FDM process is about as easy as you can get," Marangell says. "It's environmentally hazardous and a pain in the ass. You need gloves and tweezers. But in the end it's better than all the alternatives."

Those alternatives include Stereolithography (SLA), which after printing needs to be soaked in an alcohol bath and cured in a UV oven, followed by removing support structures and sanded. Finally, there's selective laser sintering, which Marangell likens to an archaeologist's excavation process, because the model is encased in a powder block you have to brush and waterjet away.

Along with making stronger parts, the basic function of the Rize One 3D printer and its Augmented Polymer Deposition process is to create a release layer between a model and support that can be peeled off as easily as a new debit card peels off the paper it was mailed with. Instead of glue dots, the Rize prints a release layer comprised of the patented Rizium One material. Post-processing for a Rize customer is the time it takes to separate the mold from the support, which is about 30 to 45 seconds.

Photo: Rize

Post-processing can take several hours to days. Because of this huge time discrepancy, Marangell and company commissioned Todd Grimm, an additive manufacturing consultant, for a white paper that presents an independent view of the "3D Printing Impact of Post-Processing."

The white paper surveyed six different companies to reveal the previously overlooked costs of post-processing. After reading it and talking with Marangell, we distilled the findings into five major takeaways:

1. Lost Production Time:

Grimm's research indicates that every six hours of 3D printing costs one hour of post-processing. The sample size is six companies, but that still equates to 17 to 100% increase of total process time.

What this also means is that while your company is engaging in post-processing, the 3D printers aren't being run, creating a bottleneck and possibly impeding time to market.

"Newell Rubbermaid runs its 3D printers at 60% efficiency, because of the bottleneck of post-processing," Marangell says. "Imagine running your factory three days a week, imagine how uncompetitive Ford would be if it was only running their car factory for three days a week."

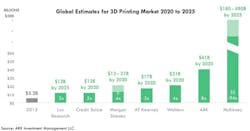

One projection has 3D printing at up to $490 billion globally by 2025; it's $6 billion now. If this efficiency gap isn't addressed, that's never going to happen.

2. Increased Labor Cost:

All that sanding and fine cutting with X-Acto knives takes more than just time; it takes people. And probably highly skilled, highly paid people, at that. The companies involved in the research reported a fully burdened labor rate cost of $30 to $100/hr. The staffing expense for running four to 10 printers is $100,000 to $500,000/ yr.

Grimm calculates that post-processing directly costs up to $50,000/yr, per printer.

3. Shallow Labor Pool

The time it takes for post-processing also factors into how much innovation you can squeeze from your R&D team. If they are manually sanding and soaking prototypes, they aren't coming up with new ideas and creating new prototypes.

"If you remove post-processing, that whole team could be working on the next print," Marangell says.

And the hiring process for your 3D printing team is also hindered. One engineering manager surveyed notes, "Post-processing is kind of an art form."

Some finer geometry requires a surgeon's touch, which an otherwise qualified design engineer may not have. So are you missing out on a conceptual superstar and settling for a serviceable jack-of-all-trades?

Marangell likens the industry settling with the oppressive post-processing factors as what happened to the U.S. auto industry in the 1970s, when tariffs were placed on Japanese cars.

"People stopped innovating until the tariffs came off," he says. "Everyone accepted it because there was no alternative. Everyone just went through the pains."

4. Unreliable Quality

The process of printing any 3D models is ridiculously advanced compared to the rather crude tools used to finish the models: X-Acto knives, sandpaper and spray nozzles. I had those tools in my high school freshman art class, a time so long ago Nirvana was still touring.

"No matter how good you are at cutting off those supports, you still leave a little amount," Marangell notes. "You change the geometric accuracy of the part. It's a nasty process."

And if the part is damaged or broken, you have to start the whole process over again, or make duplicates. This takes more labor, more printer time, and more materials.

5. Environmentally Hazardous

The medical device company canvassed by Grimm stated that their 3D printing operation was "the largest generator of hazardous waste in its entire R&D facility."

SLA models may be soaked in sodium hydroxide, a highly corrosive liquid. The dangers there should be readily apparent. And ABS and PLA materials have been found to be quite dangerous if inhaled.

"All of this stuff, if you don’t have it in a separate room, you've got dust everywhere," Marangell says of certain SLS operations. "You could see it on the reception desk, it's so fine."

These costs add up in a hurry. You have to buy the materials and dispose of them properly, along with outfitting your workers in proper gloves, clothing and breathing apparatuses. You'll also need the space to safely operate and it has to be properly ventilated.

So post-processing costs a lot, is time-consuming, and could be hazardous. What should you do?

"Since all 3D printing technologies to date require post-processing, the experienced users accommodate the added burden and make operational adjustments," writes Grimm, also calling it a 'necessary evil.'

"Suck it up" can't really be the best advice, right?

"The FDM process is about as easy as you can get," says Marangell. "It's environmentally hazardous and a pain in the ass. You need gloves and tweezers. But in the end it's better than all the alternatives."

That will be true until 2017, when the Rize One is expected to be released. It's being beta tested now, and Reebok says the process has decreased turnaround time by 50%.

Rize thinks with their new technology, they have the secret formula that will break 3D printing out of the lab and planted in offices and on factory floors. It could be as revolutionary as when 2D laser printers became commercialized in the early 2000s.

"You'll still need volume, and the lab for complex jobs," Marangell says, "but a majority of work could be done by the design engineer who wants a prototype, the manufacturing engineer who wants a tool to help his production line, and the dental tech who wants to make molds for restoration or drill guides. All of these people can have a printer and they don't have to go to a lab to get it done."

About the Author

John Hitch

Editor, Fleet Maintenance

John Hitch, based out of Cleveland, Ohio, is the editor of Fleet Maintenance, a B2B magazine that addresses the service needs for all commercial vehicle makes and models (Classes 1-8), ranging from shop management strategies to the latest tools to enhance uptime.

He previously wrote about equipment and fleet operations and management for FleetOwner, and prior to that, manufacturing and advanced technology for IndustryWeek and New Equipment Digest. He is an award-winning journalist and former sonar technician aboard a nuclear-powered submarine where he served honorably aboard the fast-attack submarine USS Oklahoma City (SSN-723).