When I was studying for my doctorate in economics, a friend was studying for his in strategy. When I asked to explain the difference between the two fields, he said it boiled down to one thing -- economists assume that companies behave optimally, while strategists try to find ways they can do better. In some corners of the econ world, that difference is pretty stark -- models assume that all companies are identical profit-maximizing machines. Elsewhere, economists admit that some companies do better than others, but don’t think about why, or how to improve the laggards.

A few economists, however, take the problem of inefficient corporate management very seriously. With differences in company performance becoming more important for the economy, these researchers are stepping up their investigations into the value of good management.

In their search for a solution to the big problems facing developed economies -- rising inequality, falling productivity growth and less national income going to workers -- researchers have zeroed in on the differences between companies as one potential root cause. A new paper by Lucia Foster, Cheryl Grim, John Haltiwanger and Zoltan Wolf shows how the productivity differences between companies have been creeping up since the turn of the century. One big concern is that a surge of new companies in an industry -- for example, the burst of high-tech startups in the late 1990s -- often tends to be followed by slow productivity growth in that industry, as most of the newcomers fail to do as well as the industry leaders.

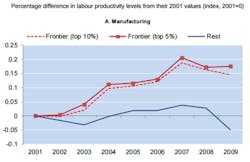

This finding corroborates the result of a 2015 study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Here, from that paper, is a graph of how the top (“frontier”) companies soared in the 2000s while the rest languished:

That’s bad news for a number of reasons. First, it can obviously be a culprit in slow productivity growth throughout the economy. If low-quality companies are kept on life support, whether by government protection, foolish investors or a simple lack of competition, it will be bad for the economy’s overall efficiency. On the other hand, if high-productivity superstar companies rise to dominate their industries -- as they seem to be doing -- it causes a monopoly-like situation that also hurts efficiency while taking income away from workers. Differences between companies could even be a substantial contributor to income inequality, as the best workers gravitate toward a few top employers.

The economy works best when a large number of companies with relatively similar productivity levels compete aggressively for workers and customers. So why are so many companies lagging behind? When I asked a friend in business, he laughed and told me that some companies are just badly managed. It’s the answer a businessman would tend to give, of course. In the past, economists paid surprisingly little attention to the issue of management quality, perhaps preferring to leave it to the strategists. But new economic research shows that my friend’s explanation is a big part of the story.

For example, economists Nicholas Bloom, Erik Brynjolfsson, Lucia Foster, Ron Jarmin, Megha Patnaik, Itay Saporta-Eksten, and John Van Reenen have a new paper that looks at management differences in the manufacturing industry. Manufacturing is an easy industry to study, because production is typically divided up among various plants. By comparing the plants with each other, it’s possible to better isolate the impact of good or bad management.

Bloom et al. teamed up with the Census Bureau to gather detailed data on more than 10,000 companies -- an absolutely enormous sample. They were also able to get specific information about which management techniques and practices each company and each plant used. The authors focused on a particular package of 16 “structured” management practices -- generally quantitative things, like tracking of performance indicators and use of production targets.

Companies and plants that use these sorts of structured management practices will generally be more productive. What was surprising is how powerful the correlation is. Structured management turned out to account for 17% of productivity differences between companies -- half again as much as differences in employee skill levels, and twice as important as use of information technology!

That’s a very big deal. And since it only represents the effect of management differences that can be easily measured, the true impact of management might be even bigger.

The really important question, of course, is whether business practices can be intentionally improved. If big, dominant companies have better management just because they can afford to throw more money at the problem, then efforts to improve management won’t do much for the economy. Smaller, less dominant companies might just not have the money to invest in making the needed improvements.

But here there’s reason for hope. A 2013 study by Nicholas Bloom, Benn Eifert, Aprajit Mahajan, David McKenzie, and John Roberts gave free management advice to textile producers in India, and found substantial positive impacts on productivity. Simply spreading information about best practices helped to make companies more efficient. It turns out that the strategy people have it right -- simply spending effort trying to figure out how to do things better can yield big results.

Why are managers in the U.S. and other rich countries not copying each other’s best practices? Companies might be forcing their employees to sign non-compete agreements and nondisclosure agreements that keep them from transferring their knowledge and skills when they move to new employers. Or perhaps management in the age of information technology is just a lot more complex and difficult than in decades past, so that only a few managers at the best companies can master the required skills. Or maybe the education system is just failing to turn out enough competent managers.

Whatever the reason, it looks like bad management is a problem that needs more attention than it’s getting.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.