When I first switched over from regular to synthetic oil for my car, I admit there was a little sticker shock at the drive-through oil change spot. It cost about double what I used to pay. Then the mechanic stuck the little sticker on the inside corner of my windshield and I saw the mileage between changes also doubled.

So I was paying more now so I wouldn’t have to later.

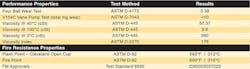

That’s essentially the idea behind Lubriplate’s SynXtreme line of high-performance polyolester (POE) –based lubricants. The company’s latest version, the SynExtreme FRH1-46, which is NSF H-1 registered and NSF ISO 21469 Certified Food Machinery Grade, exemplifies this by extending the life of the industrial machinery through which it courses, along with the added benefit of being fire resistant (FM approved using FM test method 6930).

“POEs on the thermal stability side are considered the cream of the crop of lubricants,” says Sib Hamid, Lubriplate’s corporate director of technology and the leader of the team that developed the SynXtreme FRH1-46. “These are the kinds of fluids that in a previous life I used to formulate jet engine lubricants to fly 747’s.”

If you run a food processing plant, you know any gears or conveyors in the vicinity of food need to be lubricated with an H1-certified oil. That way if lubricant incidentally splatters on a Twinkie, the only thing you have to worry about harming your body is the deliciously synthetic golden cake itself (which anyone who eats them fully accepts).

And heat is quite crucial to making these cakes and other baked goods. Tortilla ovens, for example, reach about 599°F.

Photo: BE&SCO

The fire point, defined as the temperature that a burning fluid can be sustained for at least 5 seconds following ignition, of the FRH1-46 is 600°F. The self-ignition temperature is much higher at more than 850°F.

Meanwhile, mineral-based lubricants’ fire points can range from 300-to 400°F. So if a hydraulic tube snapped, which at 3,000 psi could happen, there’s a real risk of mineral oil ending up near or on equipment that is below the ignition threshold.

Personally, I can attest to how hydraulic fluid can end up anywhere after a blowout, as I ended up spending six hours cleaning the stuff up from every crevice of a submarine engine room during my previous life.

A day long clean-up is about the best case scenario, though. A ruptured hydraulic line was the cause of the most infamous industrial food accident in America’s history, the 1991 Hamlet, N.C., chicken processing plant. Twenty-five people died and 54 were injured when a 25-ft long chicken fryer kept at 375°F ignited hydraulic fluid from a faulty hose. Granted, the fire would have been mitigated if the plant had fire alarms, sprinklers, and didn’t lock personnel in the giant facility, but it would not have started if a fire-resistant lubricant had been used.

The owner ended up spending four years in jail (sentenced to 19 years) and the company paid a $808,150 fine.

Obviously, loss of life and property should be sufficient motivating factors to investigate a fire resistant fluid. One other bonus is possibly lowering your insurance costs.

Hamid says because the fire-resistant lubricants reduce the likelihood of an accident so they also reduce insurance costs.

Being a POE, the SynXtreme also excels at protecting equipment for extended periods over petroleum-based ones.

“Mineral oil by itself doesn’t have any lubricity, while POEs have inherent lubricity,” Hamid says.

He says phosphorus or sulfur usually gets added to increase lubricity. Over time, those get consumed and you’re left with bare mineral oil.

“In the case of POEs, even without any additives, you’ll see it’s much lower on wear test,” Hamid says. The test he’s referring to is the V104C Vane Pump Test, and according to the results, the mineral-based lubricant had a 15.6 mg loss due to wear, while the SynXtreme lost only 2.8 mg.

One thing to watch out for with POEs is that they are hygroscopic, meaning they absorb water from the atmosphere. Leaving equipment containing the POE open for long periods is discouraged.

If you do decide to switch from mineral oil to this fire-resistant POE lubricant, Hamid recommends a full system cleaning. Even trace amounts would dilute the system and lower the flashpoint.

Lubriplate offers Hydroflush detergent to totally clean out the system when switching, while the old oil is still warm for best results, and then once every year to make your machinery run as efficiently as possible.

Contact [email protected] for pricing and more information.