Decry it as sweatshop labor or praise it as "an escalator out of poverty," low-wage sewing in faraway lands is going the way of the typing pool. The plummeting cost of industrial robots and the electronic cameras used for machine vision mean that serious automation is coming to even the cheapest sewn products. A high-profile example is the "SpeedFactory" that Adidas recently unveiled in southern Germany. Robots there will start turning out shoes next year, and a similar U.S. plant is in the works. The aim is to increase flexibility and reduce inventories by bringing production closer to the market.

With less fanfare, robots are already sewing bath towels and drapery pleats, yoga pants and ironing board covers. Using a computer-controlled system from Jeanologia, based in Valencia, Spain, jeans makers can substitute lasers for guys with sandpaper to distress their wares. The offending dye vanishes in a poof of blue smoke.

"Last year there were more than 70 different types of sewn products that we implemented automation and automated devices into," says Frank Henderson, CEO of Henderson Sewing Machine Co. in Andalusia, Alabama, citing examples ranging from dog collars to bulletproof vests. "There's more than you can even think about."

At the recent TexProcess Americas trade show in Atlanta, Henderson shepherded international guests around the systems on display in his substantial booth. Machines sewed pockets on jeans and interfacing on collars, assembled elastic for underwear waistbands and placed and stitched Velcro fasteners. Fed by a single human operator, each did the work of several seamstresses — faster and more precisely.

With its integration of machines and people from multiple nations, the scene suggested a more complicated and fluid production story than the popular tales of diabolical Chinese or soulless robots out to displace hard-working Americans. The us-versus-them world of Donald Trump doesn't have room for a Henderson Sewing attachment to a Japanese-made Juki sewing machine installed in a Mexican factory.

More automation does mean more sewing in the U.S. and other developed countries. But contrary to the dreams of on-shoring cheerleaders, whether economic nationalists or pro-union fantasists, robot sewing doesn't imply a return to mass industrial employment any more than high-yield seeds mean we'll all be farmers again. Automated sewing generates only a few more, and higher-paid, local jobs. It's about increasing productivity and consumer value, not putting more people to work.

At the front of the booth, a two-armed Baxter model from Boston-based Rethink Robotics replaced the operator altogether, feeding a two-headed sewing machine without human intervention. "That's $25,000," Henderson told his guests. "It doesn't get sick, doesn't take vacation." With prices like that, robots are no longer limited to making high-value items like automobiles.

Sewn-product makers are beginning to adopt "autonomous work cells," where machines do all the work. In an interview, Henderson recounts a project for a company that sews a non-apparel product often customized with logos. The client used to employ 27 people in China, shipping 9.5 million units to the U.S. each year. Transportation could take upwards of nine months and if the company picked colors that turned out to be unpopular, it was stuck. To bring manufacturing closer to customers, six vendors including Henderson Sewing collaborated to create a new U.S.-based system that starts with the customer entering the order online and ends with the box loaded onto a truck the next day.

"We cut a product, screen-printed it, flash-dried it, loaded it on to a power and free track, loaded it into 10 autonomous work cells — sewing machines — sewed the product, inverted it, packed it into boxes, depending on the order size, of small, medium, or large, taped the box, sealed the box, put the bar code on it and put it in a truck, says Henderson. "And no human touched it." Just three workers – one per shift – handle the entire process.

The investment, Henderson says, paid for itself in less than 10 months, mostly by cutting inventory costs, and the client has since replicated the system in seven other locations around the globe.

Although sewing automation does reduce head counts, cutting labor costs isn't the primary goal.

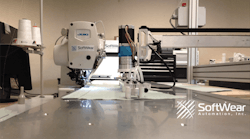

"Why would I automate something that's already cheap anyway?" asks K.P. Reddy, the CEO of Softwear Automation, an Atlanta-based startup that uses machine vision to drive precision sewing systems. Rather, automation promises quicker turnaround, lower transit costs and greater precision. That's good news for consumers and retailers, bad news for Bangladesh. The jobs at risk are the low-skilled, repetitive tasks that have been the way out of poverty for two centuries. That road may be about to close.

Softwear Automation's software tracks exact needle placement, using the thread grid and surface textures to create a topographic map of the fabric. "We're at half-a-millimeter accuracy," says Reddy. "Most humans can't even contemplate what that looks like. We can do things like sew a perfect circle, which a human can't do."

Equally important, it can do so at a price that promises a payback in two years, thanks to off-the-shelf cameras that cost just hundreds of dollars, compared to thousands only a few years ago. Chalk that up to the spillover effects of ubiquitous cell phone cameras.

Softwear Automation assumed its primary customers would be U.S. apparel makers. Instead, it found its immediate market in home goods — "curtains, towels, bath rugs, all the flat things that go into homes" — and turned to apparel only in the past three months. It's also heard from surprisingly eager foreign contract manufacturers.

Chinese companies in particular worry about impending labor shortages, as young workers flee the villages where the factories are located. "They all want to live in the cities," says Reddy. "So when I talk to these multibillion-dollar companies, they say, 'Look, we're good for the next 10 years, and then there's no talent. In the eleventh year, there's no one here.'" They want to start planning now.

The story echoes the one Frank Henderson tells, about how in the late 1980s textile jobs began leaving the South for foreign plants because manufacturers couldn't find enough local workers. "In order to grow their business they had to move offshore," he says. In our collective nostalgia, we forget how boring, regimented, and antisocial manufacturing jobs tend to be. As soon as people get a little financial security, they tend to opt for more flexibility, variety, and conversation. Robots, on the other hand, never get bored.