If you've ever wondered why 3D printing hasn't taken over even a sliver of manufacturing duties away from plastic-injection molding or traditional machining, you need only to read between the layers. These layers stack on the vertical Z-axis, and if you look really close, with an electron microscope perhaps, you'll see additive manufacturing's biggest hurdle to overcome before becoming a feasible option for end use parts.

That's because 3D-printed plastic materials, including ABS, SLA, polycarbonate or many others, don't have the Z-strength they possess along the X and Y planes.

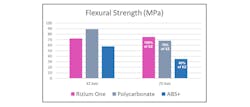

"People sometimes fool themselves when using ABS," says Frank Marangell, CEO of Rize Inc., a 3D printing startup that recently came out with a desktop 3D printer that does away with post-processing. "ABS has an off-the-shelf flex strength of 60 megapascals, and then the Z may only be 35 (Mpa)."

The Rize One is now available to the public. Check out the specs HERE.

ABS is a thermoplastic, and known as one of the stronger plastic materials with which to 3D print.

"These parts are only strong as weakest link, and weakest link—except for us—is the Z–axis," Marangell says.

He speaks forma place of confidence because Rize recently published the white paper The Importance of Z-Strength in 3D Printing, in which a third-party found Rize parts are twice as strong as ABS, and stronger than polycarbonate.

They have eliminated post-processing by jetting a proprietary release layer between the mold and part, so you can free the part simply by pulling it apart, like a new credit card off the paper. To increase Z-strength, they just do the opposite, thanks to a compound in their Rizium One material.

"One of the properties for that is the layer above is receptive to the layer below without changing the mechanical properties the engineer would want as far as heat deflection, water absorption, tensile strength, impact strength," the CEO explains.

When jetting or extruding a new layer, the previous layer has already started cooling. The part itself has molecular seams between each printed layer, reducing the overall physical integrity.

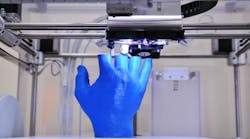

Image: Rize Inc.

For a user prototyping a model that only needs to look the part, this isn’t a problem. For example, a cardiothoracic surgeon who prints out a CT scan of a heart prior to an operation doesn't need it to withstand impact testing.

"Those photopolymers are good for form and fit, but don’t have strength for function," explains Marangell, the former president of Objet USA, which specialized in the medium.

Companies such as Stratasys, which bought out Objet, uses FDM thermoplastics to allow for function. They are traditionally are used for prototyping mechanical tooling and end-use parts.

Lack of isotropic, or uniform strength , in the print has still limited what a product development team can do with 3D printers, though, even with thermoplastics.

Photo: Rize Inc.

"The weakness has been on all the machines," Marangell says. "If you use a flex tester and break in the Z-direction, it always breaks on the line. And traditionally it's about 40% of the same test when you break it along the extrusion."

ABS can also warp, changing the geometric accuracy. And the bigger the part, the more likely it could warp.

For a company designing a full-scale product, such as a stroller company that 3D-prints brackets, these methods could have costly ramifications. What if they're testing the product and the bracket doesn't hold up to impact?

"They'll question, 'Is it a 3D printing problem, or a design problem?'" he says.

What company would leave that question unanswered and go to tooling, spending several weeks and $100,000 or more only to find there is a serious design flaw?

That company will more likely opt for injection molding, which can cost "pennies," Marangell says.

"Without real mechanical properties that match an injected molded part, you're not going to be in very many manufacturing end use part applications," he believes.

Graph: Rize Inc.

So this brings us back to why additive manufacturing doesn’t add enough yet.

"It needs functional strength in prototypes," Marangell says. "Without z-strength, you're not an end-use part, and you're not going to address the $12 trillion market. "

He points out that if 3D printing could take a 5% share, that's $ 600 billion, or "a factor of 100 from what we are today," he says.

The Rize 3D Printer will be at Solidworks 2017 Booth # 406, along with a 100 3D printed parts still attached to the molds, so guests can have a chance to see how easy the removal is and test the isotropic z-strength as well.